THE GARDEN OF EDEN - An original work of art by Adam Purple

Photography by: Harvey Wang / Written By: Amy Brost

An excerpt from: Adam Purple and the Garden of Eden, published by Traveling Light Books.

January 8, 2011, marked the 25th anniversary of the destruction of The Garden Of Eden, an earthwork that once spanned five city lots on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The fact that it is no longer extant could account for its absence from land and environmental art scholarship, along with the fact that the artist, Adam Purple (David Wilkie), lived within the city but in many ways totally apart from it. His desire to use his earthwork as a way to confront both the surrounding urban environment and the attitudes of its inhabitants eclipsed any desire he had for recognition by the art-world establishment. A search of the literature yields no substantial discussion of Adam Purple’s role as an artist, nor is he mentioned in discussions of contemporary “environmental” artists working with related themes and approaches. What one does find is a significant number of articles in the news media in the 1980s covering the controversy surrounding the destruction of The Garden of Eden. While this part of The Garden’ s existence is well documented, there has been no survey of Adam’s work, including his anti-establishment leaflets and hand-made books that recognize Adam as an important artist in his own right. Adam had no formal art training, though he did apply for and twice receive Artist Certification from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs. He considered himself an “environmental sculptor” and called The Garden his “Earthwork.” Still, he never devoted time to developing a “career” as an artist and had no art-world protégés. As such, he was not an influential part of a movement per se, but he was nonetheless an important American environmental/ecological artist. Particularly noteworthy is that, over the course of more than 10 years, Adam Purple executed a fairly large-scale earthwork in the heart of one of America’s largest cities, without financial patronage and with little more than his own two hands and a bicycle.

David began The Garden Of Eden behind his tenement building at 184 Forsyth Street. Soon thereafter, he developed his artist persona and began using the pseudonym Adam Purple. The site was located in Block 421 of Eldridge Street between Stanton and Rivington Streets, in the heart of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, occupying lots 63, 64, 65, 67, and 68. In a 2006 interview for the Story Corps Oral History Project, Adam was asked why he chose this site for his endeavor, and he replied:

“So, when I looked out my window...before the buildings on Eldridge Street were taken down, I was watching mothers sitting in the back window of a tenement building looking at their children playing in the garbage in the basement pit behind the building and I thought, wow, that’s a hell of a way to raise children, with no place to, you know, put your feet on the dirt.”

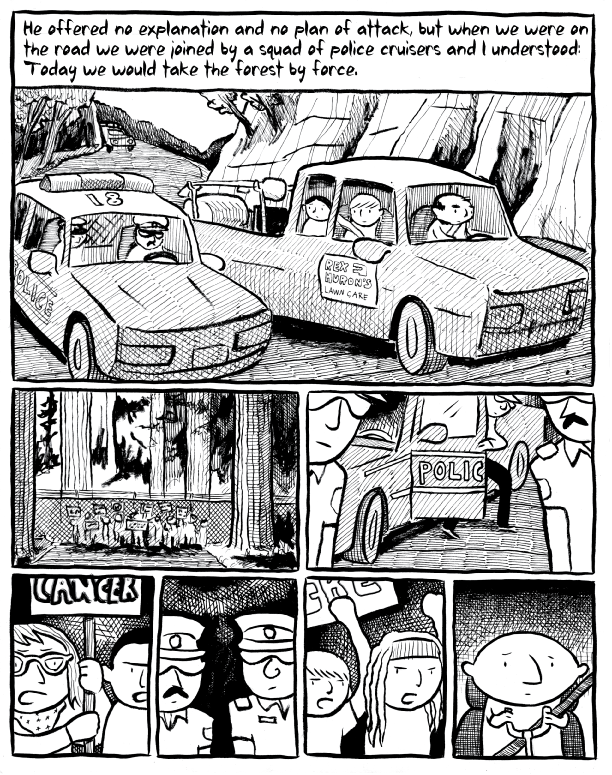

When Adam began working on the site in 1975, much of Manhattan’s Lower East Side had become a dangerous, violent, drug-ridden wasteland. In the midst of this, Adam began the process of clearing 5,000 cubic feet of debris from the two lots behind his tenement building. Adam was determined to create The Garden Of Eden by hand, without the use of engine-powered tools of any kind, not even vehicles. He argued that the automobile, along with what he called the “infernal combustion engine,” were “counterrevolutionary,” whereas The Garden would represent environmentally sound reclamation of abused land. The bulldozed, un-sifted compacted rubble was 12 to 18 inches deep, and covered each lot. Adam estimated that a 6-story, 24-apartment building would have approximately 300,000 whole bricks, many of which would be broken or pulverized during demolition. Adam dug into the debris with a pick and manually sorted out the materials in the rubble. He kept whole bricks to use for pathways in The Garden, but the broken bricks (“bats”) he considered unusable, except for use in “brick-bat calligraphy.” On the whole, he found that two-thirds of the rubble was unusable, and broken glass, plastic, etc., were discarded. However, some of the unusable material was still recyclable; the surplus whole bricks could be sold for about 25 cents each, and pieces of iron, copper, and lead could also be recycled. Wood could be burned and the resulting ash used in soil production. He twice sifted the finer debris, first with a half-inch screen, and then again with a quarter-inch screen, to separate the small gravel that could be used for walkways from the sand that could be used in soil production.

In addition to brick sand and potash from unpainted burned wood, Adam needed one more essential ingredient in his recipe for virgin topsoil – manure. To haul this material, Adam lashed a milk crate to the rear rack of his purple bicycle with polyester rope. Almost daily, he made the seven mile round trip to Central Park to bring carriage-horse manure back to The Garden. He was able to carry about 60 pounds on each trip. Wearing purple tie-dye and collecting horse manure tended to draw a fair amount of attention, and Adam called this activity an act of “conspicuous conservation.” Adam termed his combination of potash, brick sand, and horse manure the “maxi-method” of topsoil creation, and claimed that it would generate 2,167 square feet of topsoil per person per year. His corresponding “mini-method” of soil creation added square feet per person per year of topsoil, and involved composting his own vegetarian human feces, kitchen vegetable peelings, and dead leaves from nearby Sara Roosevelt Park, along with other weed prunings.

After starting The Garden Of Eden, Adam saw and admired the circular garden designs in Garden Cities of Tomorrow by Ebenezer Howard, a 19th-century utopian city planner. In Howard’s diagrams, each garden city unit was comprised of concentric circles radiating out from a civic center. These circles contained ample parkland, residences, and shops, with small factories on the outermost edge. The area between garden cities was all country and farmland. One of Howard’s plans included the prominent caption, “Illustrating correct principle of a city’s growth – open country ever near at hand….” Each of the circular plant beds took Adam an average of five weeks to make. He made the borders out of salvaged bricks reinforced on the inside edge by salvaged sheets of galvanized sheet metal. The pathways were made from the bricks that Adam chose for their superior beauty and he organized them into labyrinthine walkways and filled the gaps with sand.

In following years, more tenements were torn down and Adam expanded The Garden Of Eden to occupy five lots by 1982. The Garden grew to 15,000 square feet of flowers, herbs, trees, fruits, and vegetables, as well as 100 rose bushes and 45 fruit and nut trees. Adam’s crops included sweet corn that grew taller than he was, all manner of fruits (strawberries, apples, pears, apricots, nectarines), vegetables (asparagus, cucumbers, leaf lettuce, string beans, green peas), and the city’s largest public black raspberry patch, grown on salvaged mattress springs on a Connecticut dry stonewall. Garden snakes, brown thrushes, toads, walking sticks, butterflies, bees, and praying mantis all made their way to The Garden. Plantings included eight black walnut trees, a myriad of flowers, sweet (white) alyssum and ornamental (purple) basil to create the double yin-yang symbol, and one Chinese Empress (Paulownia) tree near its center.

Adam submitted a detailed description in his “Rubble Reclamation” article published in the Horticultural Society of New York’s Garden magazine, July-August 1979. The Editor wrote of Adam and his then-partner Eve: “With little or no help from the outside world, they have transformed a large vacant lot in one of the most foreboding areas of the lower East Side into one of the most imaginative and productive ornamental gardens in the City. […] What they lack in money they make up for by ingenuity, hard work and devotion.”