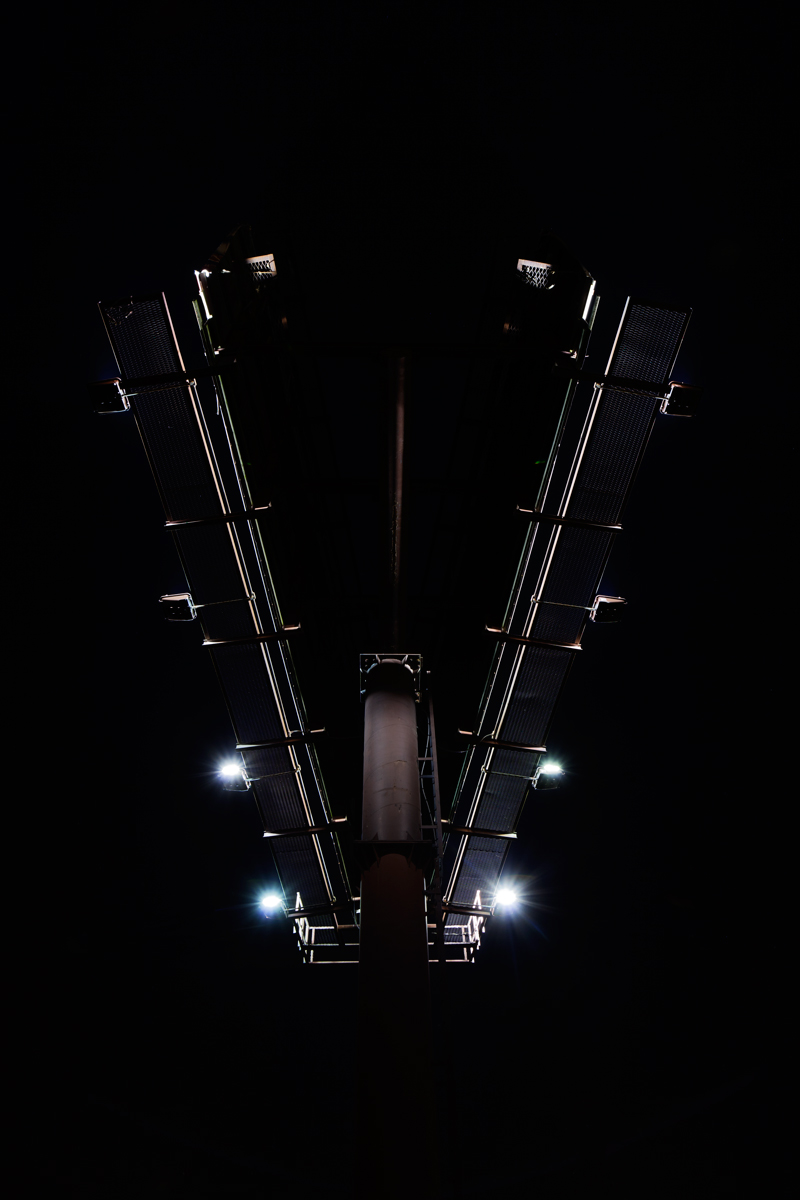

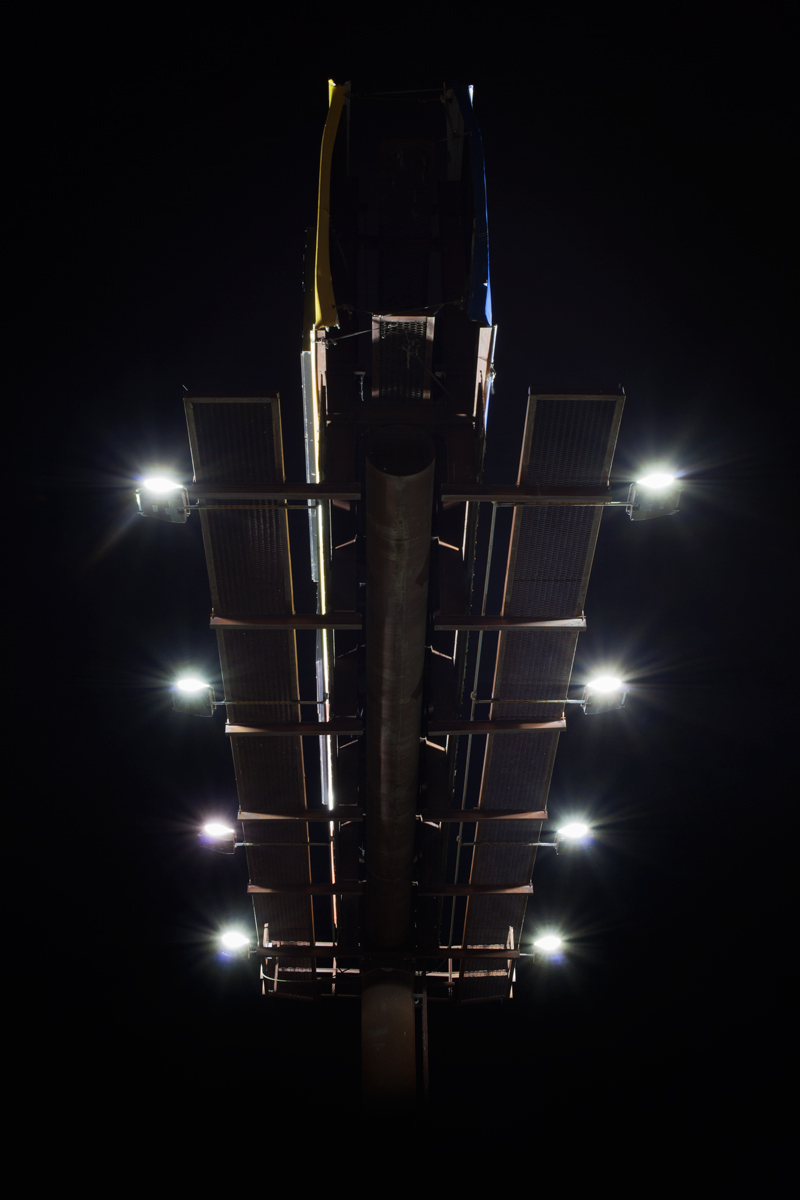

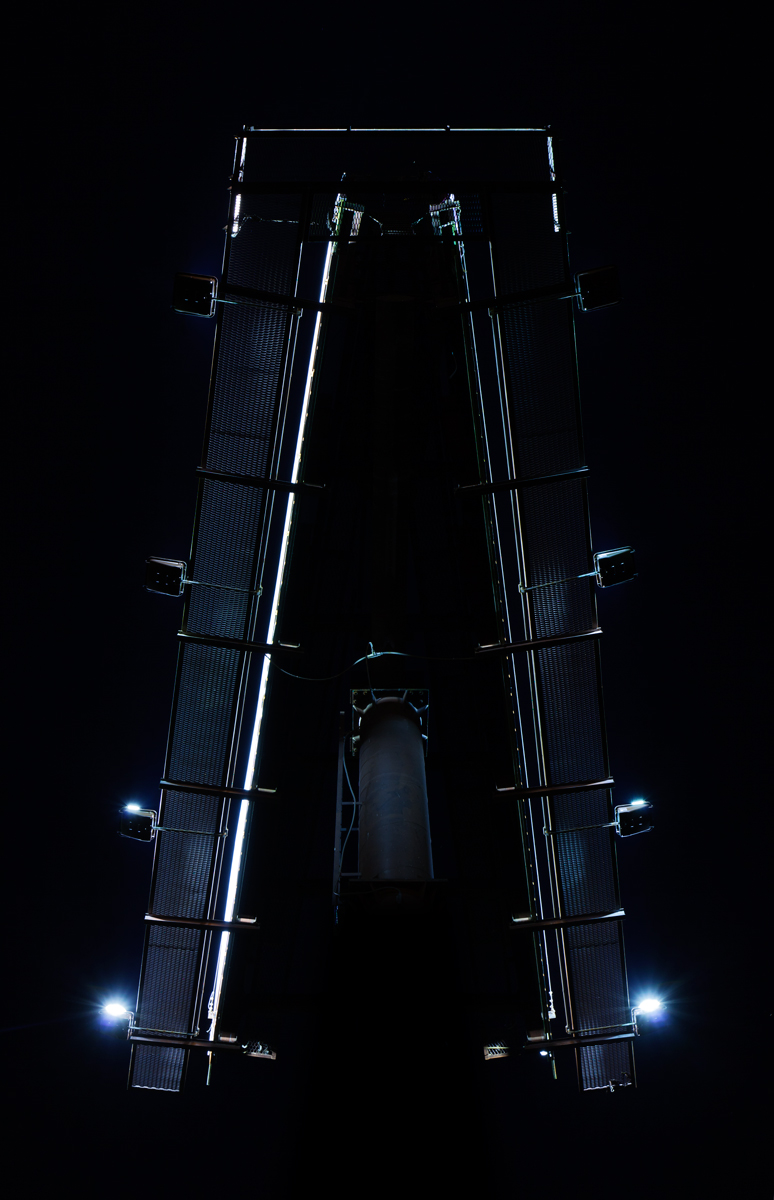

Images by: Matt Rahner

Written By: Ryan Nemeth

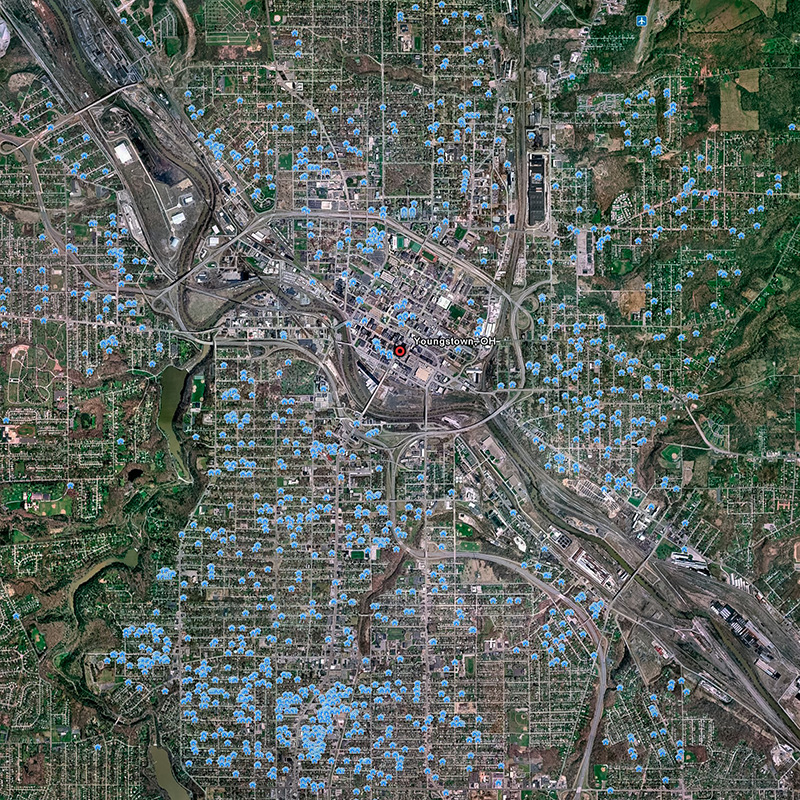

If advertisers have done their jobs, it should be glaringly apparent that billboards are man-made fixtures that are a core component of our landscape. For that matter, these attention grabbers are part of a broader media infrastructure the world over. As of 2013, it is estimated that there are as many as 780,000 billboards in America on our federal highways. Combined with billboards on both local and state roads, there are approximately 2 million billboards in the United States today. The maximum allowable number of billboards under the Highway Beautification Act is 21 structures per mile on Interstate highways, 36 structures per mile on rural primary highways, and 106 per mile on urban primary highways. Using these figures as benchmarks, Scenic America estimated that there is currently space for 10 million billboards on our federal and state highways nationwide. Regarding growth rates, the congressional research service estimated that we are placing approximately 5,000 to 15,000 new billboards a year (Scenic America, 2015). Based on these figures, we can deduce that Americans currently employ 20% of the total permitted space for billboards on highways in the United States. Could you imagine what our landscape might look like at full capacity? Spamoramalanda is all I have to say, and no that is not a word I just made up.

Applying social and urban theory, as professed by Henri Lefebvre, to billboards helps explain both the placement and use of billboards in a new light. Lefebvre argued that the most important conflict in the capitalistic economy is found in the tension between the appropriation of space for social purposes and the control of space for commercial purposes. This conflict can be described as a clash between a consumption of space, which produces surplus value, and one that produces only enjoyment and is therefore “unproductive”. Thus, according Lefebvre, the space utilized by billboards produces a dilemma of use between capitalist “utilizers” seeking to create surplus value and communities of social “users” that inhabit and occupy the same space (Klovholt-Drangsland & Holgersen, 2008). Lefebvre’s socialist theory illustrates the underlying value conflict that is often created between the common competing ends of commercial use and public access. To date, you should know that this has been a topic of debate in at least six U.S. states. If you guessed that the land use debate surrounded the placement of billboards in those states, you are right and you win a cookie! Redeem Here

Currently, four U.S. states ban billboards. They are Alaska, Hawaii, Maine and Vermont. Furthermore, Rhode Island and Oregon have prohibited the construction of new billboards in their states (ILSR, 2015). Notably, all of these states are known for their scenic beauty and derive high proportions of their state revenue from outdoor economies. True to Lefebvre’s theory, these states have placed premium “productive” values on their idle common property. Thus, the aesthetic value of land in these states is viewed as “productive” and harboring more long-term potential economic value than could be produced through advertising revenues on the land (Klovholt-Drangsland & Holgersen, 2008). What is interesting about state driven billboard bans is the fact that they implicitly advocate for a different form of commercial land use. The commercial use and coinciding value is social, shared, public, and inclusive rather than an exclusive assigned property right. Furthermore, the reform in all cases has been driven by state adopted environmental concerns.

If you do not believe that billboard bans could be effective at scale, the 2006 billboard ban in Sao Paulo, Brazil might make you think twice. Sao Paulo happens to be the fourth largest metropolis in the world. In 2006, the city of approximately 11,000,000 inhabitants banned all outdoor advertising. This ban was driven by the mayor’s “Clean-City Law” and required the removal of all billboards, transit ads, and store front advertising in the entire city. Approximately, $8 million dollars in fines were issued in order to get residents and businesses to comply. Critics of the advertising ban hypothesized that the mayor’s actions would create a revenue loss of approximately $133 million and that as many as 20,000 residents would lose jobs. Other critics were concerned that the vibrancy of the city would be lost. Fast forward to a 2011 survey conducted among the 11 million residents of Sao Paulo, surprisingly, 70% claimed that the ban is beneficial. Furthermore, virtually none of the financial ruin that was hypothesized transpired during the city’s transition. What is lasting and beneficial about the ban is the fact that many residents report noticing and admiring more of their city. The architectural features, the history, and the culture of the city have reportedly taken on a new identity as mass media messaging has been ushered out.

I know you are thinking that if I am going to write this article I should probably mention Times Square as it is the epitome of outdoor advertising in America. Let’s go ahead and cross it off the list! On the one hand, I love Times Square for the light show and spectacle that it is, it is an American landmark that should be cherished. On the other hand, it is space reserved for light pollution at best. I am certain that a billboard and advertising ban in a spot like Times Square would be an all out war for corporate lobbyist in the U.S. For those interested in the idea of reducing mass media messaging in our landscape, maybe a reasonable alternative is simply to permit advertising in tightly controlled spaces and designated areas like Times Square? However we choose to get there, I believe that we need to work on revitalizing the urban fabric and innate character of our cities. For me, this happens by creating rich urban environments that reveal the character and culture found in our architecture, infrastructure and public space as we move about our cities. The question is, could reductions in public and outdoor advertising help us cultivate new identities in relationship to our urban landscape? For me, it is certainly entertaining to envision a new way of living in our cities that does not include being bombarded by billboards and advertisements as we move about the city.

Find more of Matt Rahner's work here: http://www.mattrahner.com/

References:

- Curtis, A. (No date). Five Years After Banning Outdoor Ads, Brazil's Largest City Is More Vibrant Than Ever. Retrieved from: https://www.newdream.org/resources/sao-paolo-ad-ban

- No author, Institute for Local Self Reliance (2015). Billboard bans and controls. Retrieved from: http://www.ilsr.org/rule/billboard-bans-and-controls/

- Klovholt-Drangsland, K. & Holgersen, S (2008). The production of Bergen. International Planning Studies. 13:2, pgs. 161-169. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13563470802292042

- No author, Scenic America (2015). HBA: facts and figures. Retrieved from: http://www.scenic.org/billboards-a-sign-control/highway-beautification-act/117-hba-facts-a-figures

- No author, Scenic America (2015). Billboard Industry myths and facts they support. Retrieved from: http://www.scenic.org/storage/documents/FactSheet_Billboard_Myths.pdf.