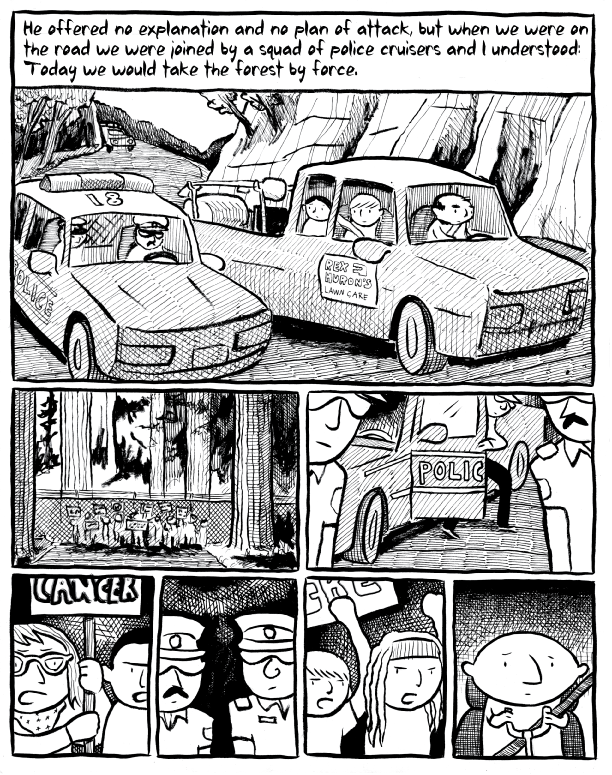

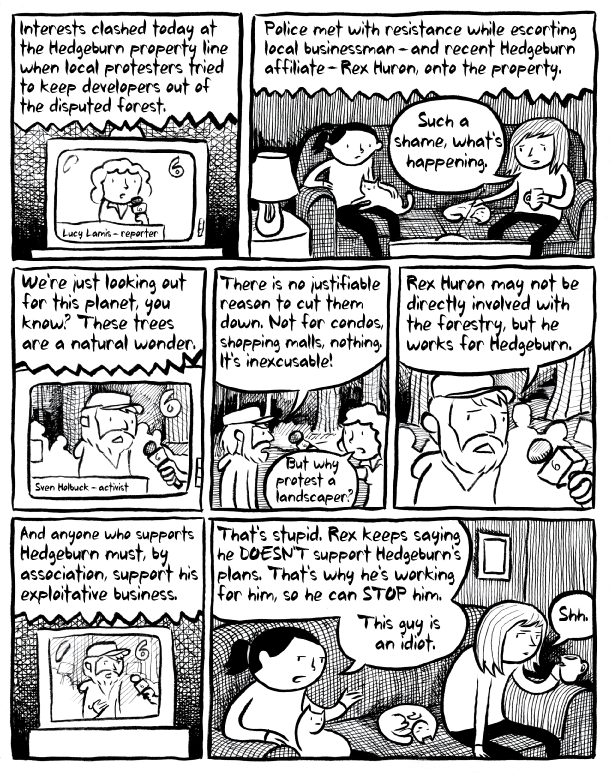

Illustration by: Breena Bard

Written By: Ryan Nemeth

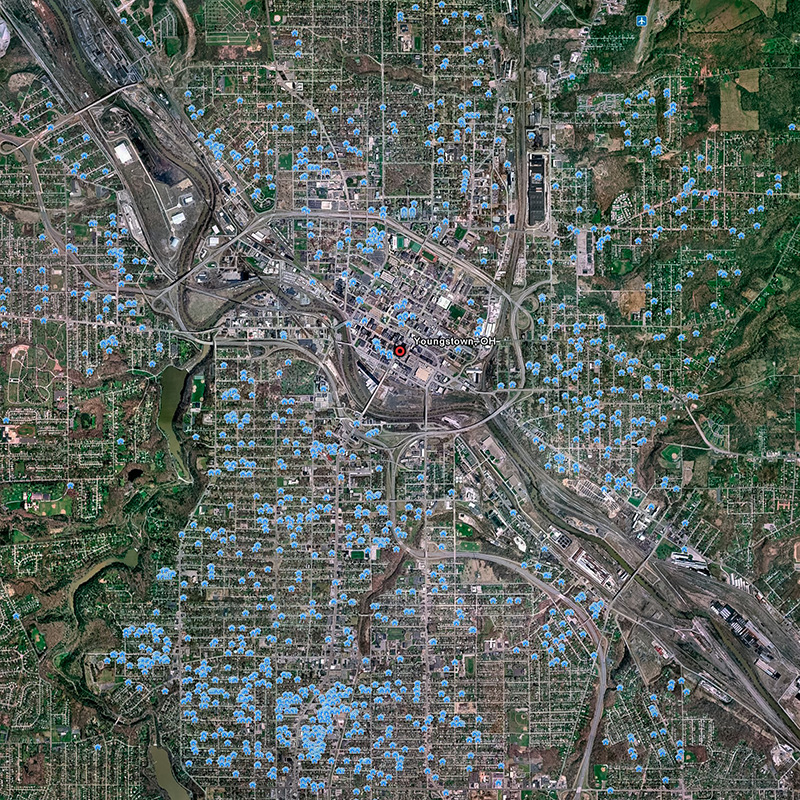

Last week, I turned on the local evening news to a story about a neighborhood activist group that was attempting to save two 100 year-old sequoia trees on a residential lot slated for a multi-unit housing development. The neighbors managed to raise $550,000 in earnest money through local contributions to begin negotiations for the purchase of the lot from the developer. I bring this story up, as it is a scenario that is becoming increasingly common in urban neighborhoods all over the globe as humans migrate to cities at an unprecedented rate. As our cities grow and become both more dense and sprawling, how much green space and old growth do we set aside from development? What land should remain off limits to preserve the character of our cities and how much undeveloped land is needed to maintain quality of life and ecological balance in our living environments? Clearly, the answer to these questions depends on where you live, who you are, and what you believe. One commonly held belief, supported by some environmentalists and urban planners, is the concept of urban density. It is the idea that cities operate more efficiently by promoting (via zoning) urban growth that is up rather than out (sprawl). The reported benefits of urban density initiatives are numerous, however it begs the question, what happens to all of our green space as we begin our urban infill initiatives? Undeveloped lots in the city with old growth trees such as the case noted above become prime targets for developers as city populations swell and space becomes more scarce and coveted.

In keeping with this subject, I recently read an article by Harvard Professor Emeritus E.O. Wilson where he proposed a radical concept. Wilson’s proposal is called the half-earth concept and he shares it with a number of colleagues and well-known ecologists. His idea is based on the belief that overconsumption and poverty could lead to the extinction of half of all species on Earth. The half-earth concept in action involves giving vastly more surface area of the earth to the rest of the plant and animal kingdom. In fact, Wilson suggests that fifty-percent of the globe should remain uninhabited by humans if we hope to reverse and stabilize current rates of global extinction. Wilson’ s argument is that we (humans) are taking up far too much of the planet and systematically eliminating biodiversity and many of the species we cohabitate with. He further develops the “half-earth” concept, by suggesting that our globe be filled with interlinked park systems that act as sanctuaries and recharge zones for plants and animals. In short, E.O. Wilson’s “half-earth” concept is rooted in the idea of population density. The underlying assertion being that increasing the density of human habitation could dramatically lessen our (human) ecological footprint.

Notably, progressive initiatives to limit urban growth have been employed in the U.S. since the fifties. In 1973, Oregon was the first U.S. state to adopt statewide urban growth boundary (UGB) laws. An urban growth boundary, or UGB, is a regional boundary, which attempts to control urban sprawl by mandating that the area inside the boundary be used for higher density urban development and the area outside the boundary be used for lower density development. Currently, UGB initiatives are scarce at best as only 3 U.S. states and a limited amount of metros have adopted restrictive growth initiatives. Yet, maybe there is something to this? Picking up on E.O. Wilson’s half-earth concept, I find the idea of density very powerful. However, it seems beyond unrealistic to suggest that we could or should suddenly corral the world’s population into dense urban living environments. Maybe urban growth boundaries (UGB’s) already serve as a happy and functional medium to push society towards Wilson’s “half-earth” initiative? As cities expand and as growth boundaries become one method for creating urban density, we must accept the fact that we will increasingly face land use trade offs and dilemmas. So the question to confront as we transform our cities is what should stay and what should go and why? If the energy savings generated by residents living in a new multi-unit high rise more than offsets the carbon offsetting capacity of two 100 year old Sequoias, should we cut the trees down to build the high rise? Clearly there is a lot to consider, my point is that we should be doing a lot of it as we charge forward into our dense future.

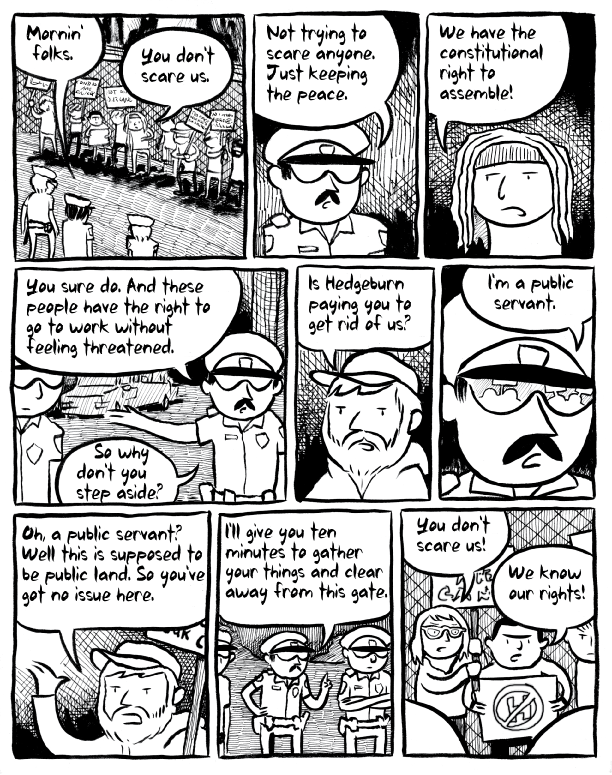

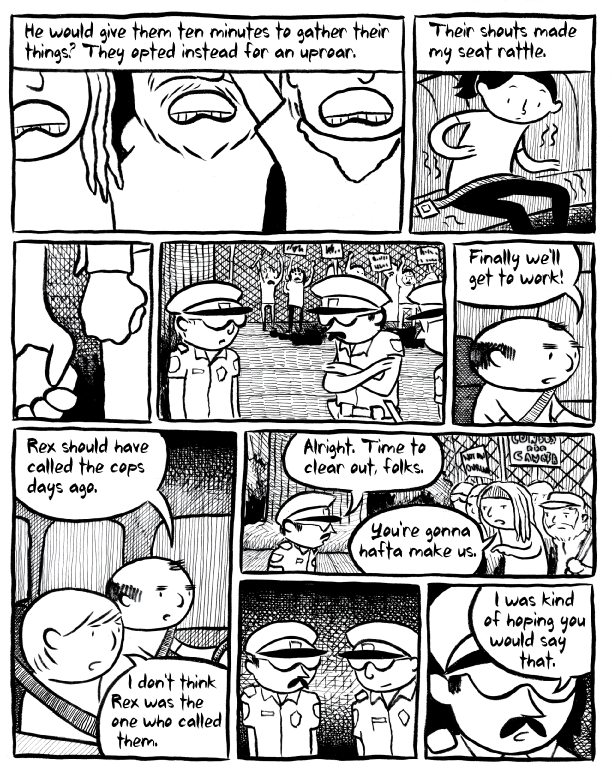

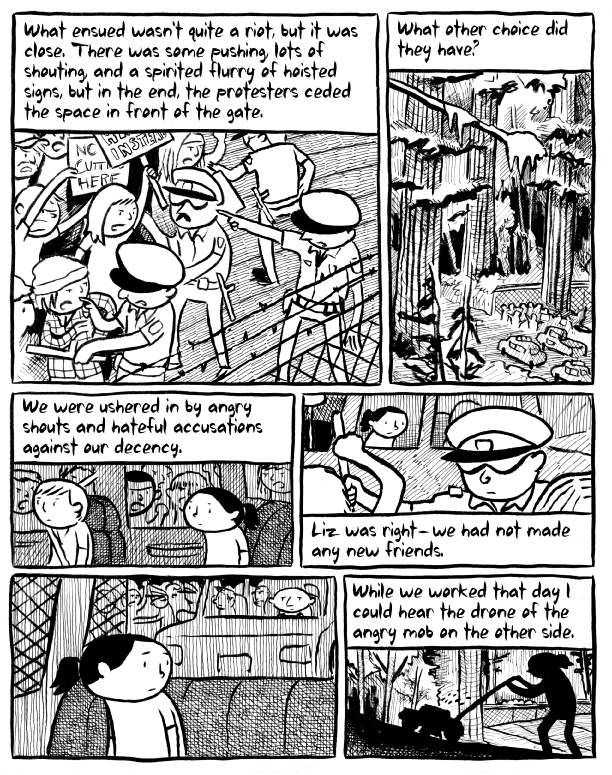

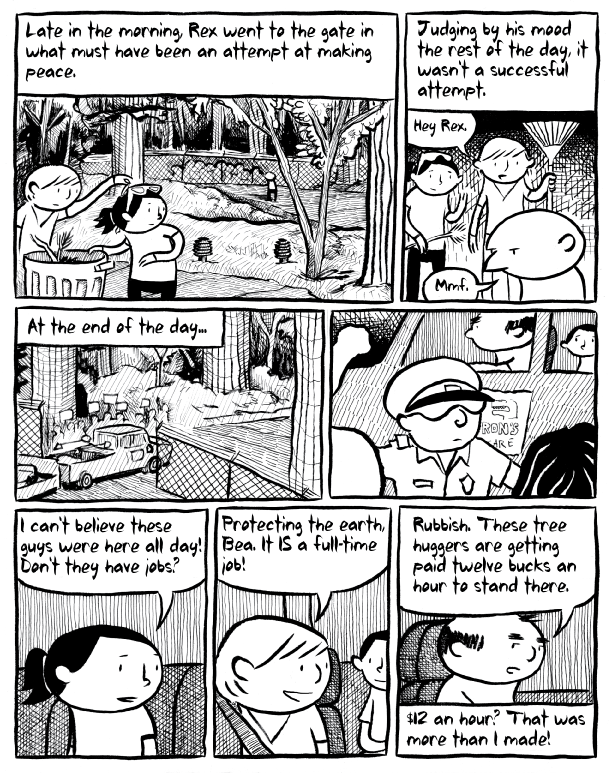

Breena Bard is a Portland, Or. based illustrator, her graphic novel the Picket Line beautifully illustrates a common and shared urban dilemma. What stays and what goes as our city grows? Here is an excerpt from her book, you can see more of the Picket Line and purchase a copy here: http://www.breenabard.com/#/picket-line/

References:

- http://io9.com/e-o-wilsons-radical-plan-to-save-the-planet-1654447315

- http://www.kgw.com/story/news/local/2015/09/14/tree-sitters-attempt--stop-eastmoreland-sequoia-removal/72258360/

- http://www.sustainablecitiescollective.com/planningphotographycom/241696/urban-density-and-sustainability

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urban_growth_boundary