Written By: Ryan Nemeth

The American West has always been a frontier of sorts for most Americans. Not only is the West still ground zero for epic road trips and custom RV sightings; it serves as space for many of us to co-exist with nature. Living in the American West for most of my adult life, I am convinced that the idea of wide-open space and unadulterated land still represents a blank canvas to most humans. This association of limitless potential embodies the essence of the American West and for that matter still remains at the core of our American identity. Furthermore, I believe that this cultural concept has made the American West potent for many generations of Americans and immigrants alike. For many, the landmass west of the Mississippi still represents fertile ground, a place of prospect, a land of dreams, and also a place to start anew. However, long gone are the days of the romantic Gene Autry and John Wayne Wild West shows. Yet, the esprit de corps of our famous American cowboys lives on as the American West continues to be tamed by a new westerner, the developer.

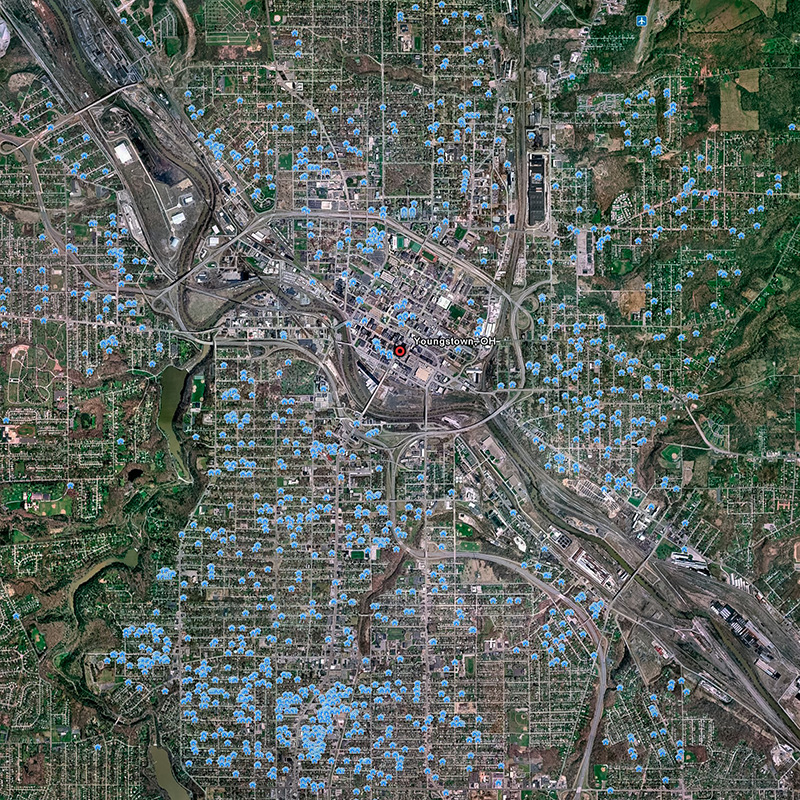

Motivated by automobile access, propelled by cheap gas, and driven by the American dream, many Americans moved west after World-War II. After all, the weather was nice, land was cheap, and this part of the States and its nostalgia represented the perfect place to start a new life. Thus, we began clearing land and making way for our new beginnings. In the act of doing so, we reduced forests, paved prairies, and dammed rivers. We replaced pristine western land with shopping malls, strip malls, suburban neighborhoods, and other needed infrastructure to feed the growth of our newfound contemporary cities. What changed and what was challenged were the characteristic environmental spaces that help preserve the identity of our American West. It is evident through many generations of urban and suburban growth initiatives in the West that the majority has still not challenged an age-old formula for urban expansion and growth. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that this formula is not sustainable in the long run. I assert that we have done very little to balance our resource consumption and environmental footprint with our desire to perpetuate new growth and inhabit space in the American West. To this day, in many parts of the West, we continue to cut and carve our way into pristine land and intervene in natural habitat.

One person that undeniable stood up and questioned these growth initiatives through the lens of his camera was Robert Adams. In fact, Robert Adams has pretty much dedicated his life to documenting and standing up to the environmental degradation and consumer creep inflicted on the American West. He has extensively documented the West’s open plains, forests, endless skies, and winding rivers. Yet, the raw beauty conveyed in his images is almost always juxtaposed with environmental overtones and metaphor of loss. Thus, Adam’s images are somewhat of a paradox as they depict the epic natural beauty of the American West simultaneous to the annihilation of that beauty by industrialization, consumerism, and pollution. As a reader, you should know that prior to Robert Adam’s and the New Topographic show of 1975 there really was no avenue for work of this nature in art photography. Adam’s legacy is that he helped usher in the concept of altered landscape as an art form. Thus, contemporary landscape photographers know a world before and after Robert Adam’s. We should be thankful that he helped secure a seat at the table for environmentally driven art photographers.

Given his stellar career accomplishments, it is easy to consider Adam’s legacy and his role in context to the places that inspired his work. In doing so, I cannot help but reflect on the spirit of the cowboy in the American West and wonder just how Robert Adam’s fits into this picture? Cowboys are notorious for their land driven lifestyles, their freedom to roam, rugged independence, as well as their ability to break the rules and buck the system. I would argue that within the context of landscape photography, Robert Adams is all of these things and more!

I had the chance to correspond via mail with Robert Adams about the environment and photography and here is what he had to say:

1. It is apparent in your work that you have a strong emotional bond and connection to nature. Can you attribute your affinity for the natural world to someone or something you have experienced in your life?

My father, bless him, first took me on hikes in the woods when I was three... he carried me on his shoulders. They are among the first memories I have. We went on to share a love of the outdoors - hiking, camping, river running - for over sixty-years.

The other person who has guided my understanding of nature is my wife Kerstin. She is from Sweden where nature is practically a religion. She’s taught me particularly about animals and their sacredness. She’s just been calligraphing a beautiful aphorism by Porchia, “Even the smallest of creatures carries the sun in its eyes.”

2. Do you feel that the genre of landscape photography has changed over the course of your career? If so, could you elaborate on the changes that you perceive as occurring?

There have been relatively different emphases in landscape photography almost from the beginning. At one extreme there has been a focus on aesthetic pleasure for it’s own sake, and at the other for the sake of understanding the world. A lot of work is somewhere in between, but there is always going to be a tension.

3. I know that you earned a Doctorate in English; yet, you chose the photographic medium as your preferred method for speaking out about the environment and communicating about landscape, why?

I came to feel that my gifts were primarily visual. Besides, it was more fun to be outside! Certainly, I could never have written at the level of Wendell Berry, Edward Abbey, or John Hay.

4. Much of the work you have produced demonstrates an intimate understanding of place. Do you feel that knowing or having a sense of place impacts your photography? If so, how?

I believe that my work is more truthful where I have watched the hours and seasons pass. It helps me to recognize what is characteristic. And occasionally to hear... There is no way to say this without sounding foolish... the voice behind the other voices.

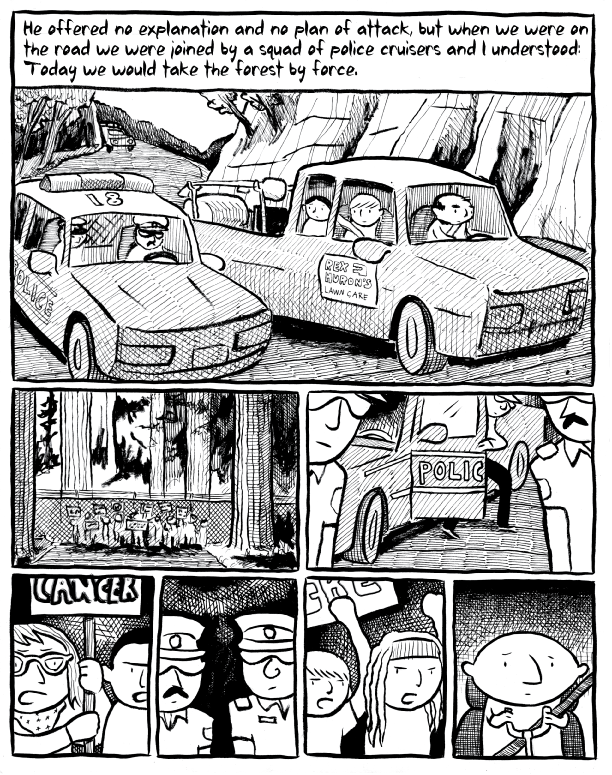

5. Throughout your career you have been actively involved in taking a stand against clear-cutting and logging activity. In fact, much of your career has been devoted to preserving the health of forests that surround your immediate living environment. What other current environmental challenges are important to you?

Locally, I worry, along with some of our neighbors about LNG (natural gas) terminals and coal and oil trains. Nationally, my concerns are numerous - fracking, mountain top removal, etc. But, behind all of these issues loom the stay-awake-at-night terrors; overpopulation, nuclear weapons, and climate change.

6. In keeping with the topic of activism, you have suggested through prior conversations that speaking out about the environment can be a solitary and isolating experience. I believe that this concept provides a powerful perspective on the process of change through activism. Would you elaborate on this idea?

Well, there’s some accuracy to the Turkish proverb that states, ”Tell the truth and be driven from nine villages.” Though as long as you do not make too much trouble, your opponents don’t come looking for you. Though, they don’t come asking you to be on their commissions either. But, the amount of activism that Kerstin and I have attempted has largely been limited by time and energy.

7. Some photographers produce their work around a central theme or concept. Others shoot freely and then edit their work to identify common themes that can be consolidated and grouped together for a series of work. Can you elaborate on your process for creating a new body of work? How does the creative process work for you?

A lot of projects seem to start with more or less accidental discoveries, then you build on them! Of course, even an afternoon of random exploration is shaped by your life’s values. John Sarkowski had a wonderful and funny piece of advice when he thought something was stuck, he would say, “Just kick the tripod a little.”

8. In thinking about the future of environmental activism through the lens of photography, what advice might you offer to those of us who are trying to change the world through imagery? Is there reason for hope?

I wish I had some practical advice. When I look back over Kirsten’s and my life, it seems that we were saved by luck and discipline and the help of family and friends. When it looks dark, I sometimes remember a line from Pablo Neruda’s speech: “I saw so many honorable misfortunes, lone victories, and splendid defeats.” Also, I should mention that once or twice I have repeated to a photographer a blessing that was formulated by the Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno: “May God deny you peace, but give you glory.” He was thinking, of course, of Don Quixote.